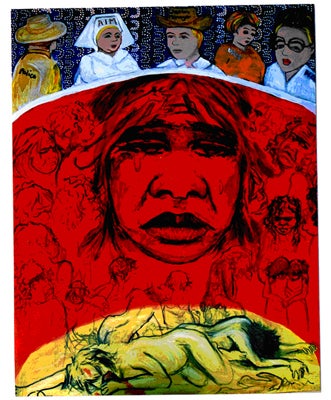

Women's Lament , Kunyi McInerney, 1999

This painting is our Oodnadatta History. The people on the top row are the police, Australian Inland Mission nurse at the Oodnadatta clinic/ Hospital, the station manager, the United Aboriginal Mission missionary, and the social worker. All these people are responsible for removing the children from the families and their culture and area.

The red sand is the sand hills shaped like a large a football oval and in the centre is the clay pan where we used to have the school sports day. The people told us when the wind gets inside this large oval it makes a wailing noise and they say that noise is the families especially the mothers crying for their children who were taken away. The mothers and grandmothers were so frustrated and desperate that they would strip their clothes off and cut themselves with sharp rocks, and fall down whaling for their children- some never to be seen again. This large painting was used on the stage when the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commissioner came to Adelaide.

I spoke to my mother for the first time when I was 27 years old... The time was 11.37pm on Friday the 15th of September 1978. I had just arrived in Tennant Creek from Sydney where I`d lived and worked for the previous twenty seven years.

I pushed open the tired wrought iron gate of the house and walked in darkness along the concrete path. As I did, the front door opened and a young boy and girl ran out of the house yelling ``Dougie!``. Who the hell is Dougie? My name is John! Did I just travel two thousand kilometres to the wrong address?

Before I could turn around and walk back out the gate a young woman was walking down the path towards me. She peeled the two young ones off my arms and left leg and took my hand as she said, ``Mum`s been waiting forever to see you``. My eyes followed the path in front of me to where I saw the silhouette of a woman standing in the half light of the open door. Her hands were clasped together in front of her body and she stood perfectly still. Even in the darkness, I could see tears rolling down her chubby cheeks. She held out her arms to embrace me and I walked into them. We held each other for the longest time. I was home.

- John Williams Mozely

“I was adopted six weeks after I was born and believe I was taken by undue pressure because even when my biological mother was passing away she told my sister who was there that there were more and they were not the only ones. She had little yellow tabs in her diary with Link-up phone numbers all over them.”

– Christopher Mason

“A young woman who was having a relationship with a white man falls pregnant, he dumps her and his offspring. She, poor girl has nothing and very little support from anyone, parents are diabetics. She attends local hospital, baby due New Year's Eve 1965. She is left for 3 days in labour, finally; baby delivered by forceps, bruised black and blue, not breathing. After 20 minutes fed by oxygen he came around. She did not have him for days, he was too injured.

She asked about her baby and was told he was hopelessly crippled plus cerebral damage. She took it, they spoke the truth. She then had a social worker write and ask C.S.V. about her little son 28th March 1965. She was sent a letter dated 22nd March 1965, that Paediatrician at R.C.H. had made him a State Ward. At 10 months he was placed in foster care. The reports on this lady were not very flattering, and on the baby's records it states: find parents for this child.

He stayed in foster care until 21 months, when we came along. We went to see him. My husband squatted down and called the little boy's name. The child had not a thing to play with. All that was in the yard was a pile of blue metal stone. Suddenly the child scooped up a handful of these stones, went over to his soon to be chosen father and placed them in his hand. He had nothing but these stones and he gave them, “I'll be darned we said”. With that he had a family.”

– Ron and Marie Cox, Jonathan Cox's adoptive parents

Sacred Mothers

Both my Mothers were stolen

In a very profound way

First, the Mother Land of my ancestors

Then, my own Mother that fateful day.

The longing was always strong in my heart

Often caused me to flee, “abscond”

I needed to be with the ways of my own

That is where I belong.

The innate knowledge of my ancestors

The land, the loss and, the chains

Could ne'er withhold the spirits strength

Of which, all my life is aimed.

I broke through your incarcerations

The leg ties, barred windows and doors

That 'Christian' cruelty and state abuse

Wasn't our way; Shouldn't have been yours.

“Wilful” against crown and state controls

Vowing my own all true worth

Fought alongside the rest of us

Whilst you mongrels perfected your worst.

So many were killed or broken

Yet still, many of us survive

And, we rise the ways of our ancestors

We, the new generations with pride

Claim our own return to this nation

Our heritage, our culture, we stand

And, live within future generations return

Our Mother's spirits to this sacred land.

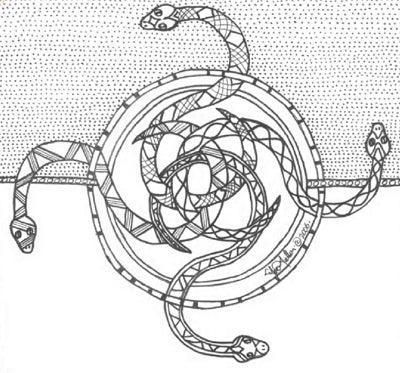

- Yveane FallonPicture: 'Rainbow Serpent' by Yveane Fallon

My natural mother was the eldest of six brothers and sisters. She was also the fairest. Her name was Mary Barbara Williams. [Like] so many other Aboriginal kids, her birth was never registered. All that's known from archival records is that she was born at Alice Springs on or about the 28th of December 1933. Her mother was Ruby Foster and her father was Elias Jack Williams. Jack was a Western Arrernte man and was raised at Hermannsburg, a former Lutheran Church Mission one hundred and forty kilometres west of Alice Springs.

Hermannsburg Mission was established in 1877 in the traditional land of the Western Arrernte. Over time, Luritja and Pintubi people were brought into the Mission as the “civilising” mission spread further and further into the Central Desert area. Hermannsburg was handed back to its traditional owners and custodians by the Church in 1982 and is now called by its Arrernte name, Ntaria.

Jack, as he was called, was the son of Johannes Ntjalka and Maria Kngarra. While Jack claimed Mum as his daughter, he was not her natural father. Her real father was apparently some white fella whose name is not mentioned by the old people at Hermannsburg. This was the way things were! While her brothers and sisters grew up with each other at Hermannsburg, my mother was raised by a Northern Territory policeman at the old Heavy Tree Gap police station in Alice Springs. His name was Bob Hamilton and although he was not my mother's father, he 'grew her up' from when she was a toddler. Bob was a white fella. I would have liked to have met him but he died in 1963, long before I ever knew his name or who is was.

Notwithstanding the fact he was a police officer, old Bob apparently couldn't stop the police or Native Welfare Board from taking my mother. My mother was thirteen at the time. The year was 1946... Unlike kids taken to the Bungalow, other Aboriginal children from the Northern Territory who were placed in institutions such as Garden Point on Croker Island, St Mary's Home in Alice Springs, or Groote Eylandt Home had a more than even chance of remaining somewhere within the Territory. This was the case with Mum's brothers and sisters who were also taken away one by one and placed in various institutions in the Northern Territory. When they were old enough and no longer under the control of the Native Affairs Department, they all managed to return to Hermannsburg to live.

My mother's ultimate destination, unknown to her at the time, was the Church Mission Society home at Mulgoa near Penrith New South Wales, more than two thousand kilometres by rail from Alice Springs.

After two years in the Church Mission Society home at Mulgoa my mother was deemed sufficiently educated and trained to commence employment as a domestic servant. It was apparently of little concern to the Church Mission Society or government that she was functionally illiterate. She began work at fifteen with Normanhurst Private Hospital in Ashfield. After working here and later, as a domestic on a sheep station near Tamworth my mother sought permission to return to the Northern Territory. After being told she didn't meet the minimum educational requirements for the Air Force in Alice Springs Mum returned to live in her Mother's county - Warramungu country – in Tennant Creek. Her journey home had taken her nine years.

- John Williams Mozley

My story is about a mother and daughter both victims of those nasty folk called the Aborigines Protection Board, (the APB). Lily- born 1910 and her daughter Marjorie, born 1925.

Both were taken from the community. Lily at the age of 14 commenced service to Mrs S. G. W in August, 1921. Lily was found 'un-suitable' and came back to the community in 1922. Three years later, the APB sent Lily to Mrs. A. J. C. In June, 1925 Lily was sent home pregnant, where she gave birth to a baby girl she named Marjorie. Her babe was taken by the APB and placed in the care of Aunty Elizabeth, my grandmother, who raised Marjorie. Lily returned to Mrs C., falls pregnant again and so is returned to family for good in November 1928.

Marjorie was raised by Lily's Aunt Elizabeth until she was eight, at which time the APB inspectors came and took child away to Cootamundra Aborigines girls home. That was the last time Lily saw her daughter. Later, Lily married had other children. Lily later died not knowing where or what was happening to her daughter Marjorie.

Lily's children searched for many years trying to find their lost sister, no luck because APB records were not available to Aboriginal folk at the time. Then a change came on the scene Marjorie who had married and raised her own family, was finally found by her family after 70 years. A re-union was arranged by her brother and sister, to take their sister back to Karuah Reserve from where she had been taken from all those years ago.

The sad part is that Lily had not known where her daughter was, but we have discovered that the girl I knew as Marjorie was on occasions travelling north by car with her daughters passing through Purfleet Reserve to spend Christmas with her only son Ken at Port Macquarie. Not knowing her Mum who was alive and lived on the Purfleet Reserve at these times.

Like many other Aboriginal boys and girls, we were used as slave labour. Now the government is offering me peanuts in recognition of wages and child endowment owed to my mother, the cheek of the government bureaucrats. There is no justice for Aborigines in this country at present, hopefully such will come soon after such stories are told.

- Les Ridgeway

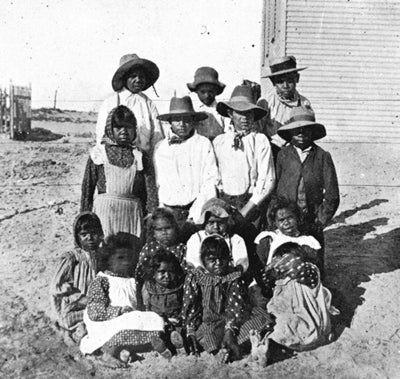

Photograph: 'A group of Aranda girls',

Photographs of Australian Aborigines, Australian Aborigines Friends' Association, 1936.

To me they were surrogate mothers when I were growing up; when I left school and began work they were more like really special friends. The thing they stressed to us always was that you are as good as, if not better than, everyone else. It is up to you. I grew up with a very, very positive outlook on life because of that.

- Esther Bevan, interview with Siobhan McHugh

The Shelter

Row upon row we cowered

Between sheets threadbare but crisp

And brittle like sheets of white glass

Tucked too tight by our own childish hands

Tiny fingers trained on chilly mornings

In the art of “gaol corners” we were told

“This is how you'll make your beds in prison'

Some of us not yet ten years old

But we'd be making beds in gaol

It was not inconceivable

And how was I to know then

That gaol would be an improvement

On the sorry protection

Of Glebe Metropolitan Girls Shelter

- Vickie Lee Roach

The Powers that be during my incarceration in the Coventry Girls Home, told my sisters and I that we were no longer to speak my father`s language, Bundjalung, and it was belted out of us until we no longer spoke it. We were then told every day that out parents did not want us- that's why you are here.

It was not until I was old enough and left the home, that I was confronted with the truth and learned of the government policies and practices that brought about the children being removed.

- Elaine Turnbull

Photograph: Girls Dormitory, Cherbourg, 1959.

Photograph reproduced courtesy of the State Library of Queensland.

The Warm Bed

I was taken by white man

When I was six

Taken from our warm bed

And they left behind our sis

For the bed was surely crowded

And the hut had a dirt floor

But the warmth and the love there

We had no more.

With their crisp sheeted single beds

We were told we were lucky as can be

To be brought up by white man,

And they said we were free

Well the years passed by,

And for my family we cried,

To be back in that warm bed

Oh, just for a while.

For the white family gave us

What they long for

A good education, material things

And we had it all, but,

No-one will know the pain,

Of the longing for.

Well more years passed by

And now we still cry

For our dad and mum

Had suffered until they died

Our big sister still lives,

The one they left behind

To snatch her siblings from her

And her pain will never die

Can't you see white man?

For the damage we dread

We will never again

Be as one with our family

In that lovely warm bed

- Suzanne Nelson

Photograph: 'The touch of civilisation',

Photographs of Australian Aborigines, Australian Aborigines Friends' Association, 1936.

Photograph courtesy Ivan Copely

It just happened that my mother came once to see me, but she was sad, I could understand, she was upset. After being taken as a small child and going to see her as an adult, well, she said that I wasn't her daughter. You know, with all the hardship and the loss of her child,

I suppose she felt it very bad that way, and she never, never talked about it. She just looked at me and said, 'you're not my daughter'. It was a long time you know? I mean taking a child away at a small age and then going back to see the mother, as an adult well,

she would be shocked I suppose, thinking, oh you're not my daughter. That was the first and the last I've seen her.

She didn't even let the other old people [know that] she had another daughter because it hurt her. She was broken up inside. She never mentioned she had another daughter. It's just recently, when the people say, “oh, it's your mum and all this and that”,

they always say, “oh, she never said anything about it, she never told us”.

Well I said, because she was upset and she had a broken heart.

And that's how she went to her grave, with a broken heart.

- Phyllis Bin Barka, interview with Siobhan McHugh

Painting: 'The Box', Kunyi McInerney, 1994.