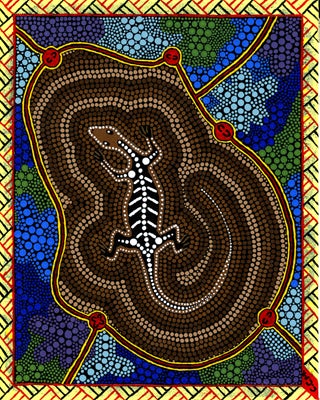

'This painting is the story of us children coming home', Chris Mason, 2007

'Our totem is the goanna and is culturally significant with the black and white in the centre representing assimilation and how we have learnt to live within the framework of white society. The different shades of colour in the middle show no matter the colour of our skin we are one and do belong. The border represents Link-up who made this story possible and helped bring us home. The red represents our Aboriginal bloodline that links us together. With the outer colours showing the world and the bright future full of possibilities.

The symbols are of women and men sitting symbolising Chris and his sisters. 'Near the head of the goanna is my eldest sister, she's at the head of the family- then Lynn, Debbie and Karen, myself and my youngest sister, Roberta down the bottom.

'Jangali' is my Aboriginal name

Siobhan McHugh: So when you go back to where you were originally from, do you still feel a sense of connection to that country?

Daisy Howard: I do, yes. When I go back there I still feel it. I cry too. Like I say, I would rather be brought up that way and knowing everything, than being brought up the other way and not knowing anything. I think it hurts more to know now what happened because, I mean, there's nothing we can do really.

Siobhan McHugh: If you went back to live there would you live in the Aboriginal way or the western kind of European Catholic way, would you do things the traditional custom way, or not?

Daisy Howard: No, I think I always be a Catholic. Like in town and go to Church and things like that. I don't think I'll ever forget that. I went a few times with the people from the language centre. I mean I just pick up a few words here and there - like my Aboriginal name. 'Jangali' is my Aboriginal name.

I feel sad at times not meeting my mother, especially my mother, but in the long run, now that I grew up and I had me own children and I battled hard with my children, so what was more concern was my children. I battled hard for them; I didn`t get any help from anyone. So that`s all I`ve got, is my children. That`s the happiness I`ve got from all that - my children come first, and I think it`s a wonderful thing to have children.

I`ve had my children and looked after then and gave them caring and everything, but I didn`t speak about my background because I never knew anything about it. The minute you talk about these things some of the Europeans say, `oh bullshit`, and all things like that. And that hurts us, you know? They didn`t go through it. And that was the government policy, and I think that the government should recognise these things. But the Prime Minister don`t understand anyway.

- Phyllis Bin Barka, interview with Siobhan McHugh

Trust- no

Helplessness

Endurance

Suffer of children

Toleration

On my own

Loss of identity

Evil people

Not letting me go

Going to another place

English voices

Nervous

Endless suffering

Racism

Action

Teasing

Incorrect to do that

Option- no

No one understood

- Tahlee Connors

Sad Children

Terrified

On my own

Lost my identity

Evil men

Not feeling happy

- Keidan Bates

When societies or cultures collide it is often the children who suffer most. For Aboriginal children, the British colonisation of Australia was no exception. During the first 120 or so years of European settlement, successive governments either permitted or actively pursued policies of removing Aboriginal children from their parents and communities. The implementation of these policies represents one of the most shameful episodes in the treatment of my people by white Australians.

Although frequently motivated by good intentions, the removal of Aboriginal children was to embitter relations between the two peoples and cause enormous pain and suffering to the children and their parents. The damage caused to parents and families persists today.

The past can not be changed but some of the wounds can be healed. The process of reconciliation must state with a candid recognition of what took place- the forcible removal of many Aboriginal children from their parents and communities.

- George Toongerie

One of my earliest memories was the next door neighbour calling me a black bastard and my adoptive parent's reaction. Until then I was oblivious to skin colour. That when the explanations started and to my adoptive families' credit they tried so hard to bring me up that I feel I owe them so much for the grief I have caused over the years. I put my behaviour down to an identity crisis and all the drama one experiences in trying to find their way. I was looking in all the wrong places only to find trouble. All I found were drug addicts, alcoholics and criminals but no acceptance. This led to violence, anti-social activity, promiscuity and other risk taking behaviours only to find no relief. Death couldn't come fast enough but all there was gaol and hospitalisation in which case I am still in.

These activities stopped and I changed completely because I found my biological family and found where I fitted in, in the world. I finally felt I knew who I was and didn't have to be good enough for anyone else. I know I survived the hard part and now it is all about the good stuff. Second chances do come along for some and if and when they do they must be embraced with both hands. Link-up made it all possible and I am forever thankful. The next important thing for me to do is meet my aunty and go to Bre, my country, and feel the feeling I long for. This day will happen and it keeps me going through the hard days. My culture is important to me and I enjoy learning about it and look forward to learning more ever day.

– Christopher Mason

When I was about four or five, I asked Mum why I was different to her, my father and my brother. Even though we lived together as a family and had the same surname, I knew something was amiss because I was black and they were white. For a long time Mum wouldn`t answer my question directly. In the end, to shut me up I think, she told me that I was `different` because ``God left you in the oven too long``. What did this mean? Who was this God fella?

About a year later, I raised the question with Mum again. My insistence paid off. Mum and Pop sat me down in the living room one night and solemnly told me that there was something they wanted to tell me. We had just finished dinner, the wood fire was crackling and the radio was tuned to one of the weekly serials. Pop switched the radio off. This must be serious I thought. He eventually spoke up and said gravely ``Son, the reason you`re different is because you`re adopted``. Mum was close to tears in anticipation of what effect these words would have on me. I turned to them both and said,

``So, if you're adopted, it means you're black, is that right?``

After several prolonged conversations about what being adopted meant, I realised, selfishly I suppose, that I must have another mother and father, perhaps other brothers, sisters, uncles and aunts too. Perhaps even another grandma? Not that there was anything wrong with my adoptive family. My adoptive parents grew me up with all the love and material comfort that was their`s to give from when I was seven months old. They love me and I love them, as a son should. At that time, however, the word ``Aboriginal`` was uttered in clandestine whispers.

– John Williams Mozely

Jennifers Story

My grandmother, Rebecca, was born around 1890. She lived with her tribal people, parents and relations around the Kempsey area. Rebecca was the youngest of a big family. One day some religious people came, they thought she was a pretty little girl. She was a full blood aborigine about five years old. Anyway those people took her to live with them.

Rebecca could not have been looked after too well. At the age of fourteen she gave birth to my mother Grace and later on Esther, Violet and May. She married my grandfather Laurie and at the age of twenty-three she died from TB. Grandfather took the four girls to live with their Aunty and Uncle on their mother's side. Grandfather worked and supported the four girls.

Mum said in those days the aboriginals did not drink. She often recalled going to the river and her Uncle spearing fish and diving for cobbler. Mum had eaten kangaroo, koala bear, turtles and porcupine. She knew which berries were edible, we were shown by her how to dig for yams and how to find witchetty grubs. My mother also spoke in several aboriginal languages she knew as a small girl. The aboriginals had very strict laws and were decent people. They were kind and had respectable morals...

Years later Grandfather told my mother a policeman came to his work with papers to sign. The girls were to be placed in Cootamundra Home where they would be trained to get a job when they grew up. If grandfather didn't sign the papers he would go to jail and never come out, this was around 1915. My grandfather was told he was to take the four girls by boat to Sydney. The girls just cried and cried and the relations were wailing just like they did when Granny Rebecca had died.

In Sydney my mother and Esther were sent by coach to Cootamundra. Violet and May were sent to the babies' home at Rockdale. Grace and Esther never saw their sister Violet again. She died at Waterfall Hospital within two years from TB. My mother was to wait twenty years before she was to see her baby sister May again.

Cootamundra in those days was very strict and cruel. The home was overcrowded. Girls were coming and going all the time. The girls were taught reading, writing and arithmetic. All the girls had to learn to scrub, launder and cook.

Mum remembered once a girl who did not move too quick. She was tied to the old bell post and belted continuously. She died that night, still tied to the post, no girl ever knew what happened to the body or where she was buried... Some girls were belted and sexually abused by their masters and sent to the missions to have their babies. Some girls just disappeared never to be seen or heard of again...

Early one morning in November 1952 the manager from Burnt Bridge Mission came to our home with a policeman. I could hear him saying to Mum, 'I am taking the two girls and placing them in Cootamundra Home'. My father was saying, 'What right have you?'. The manager said he can do what he likes, they said my father had a bad character (I presume they said this as my father associated with Aboriginal people). They would not let us kiss our father goodbye, I will never forget the sad look on his face. He was unwell and he worked very hard all his life as a timber-cutter. That was the last time I saw my father, he died within two years after.

We were taken to the manager's house at Burnt Bridge. Next morning we were in court. I remember the judge saying, 'These girls don't look neglected to me'. The manager was saying all sorts of things. He wanted us placed in Cootamundra Home. So we were sent away not knowing that it would be five years before we came back to Kempsey again... I had often thought of running away but Kate was there and I was told to always look after her. I had just turned eleven and Kate was still only seven. I often think now of Cootamundra as a sad place, I think of thousands of girls who went through that home, some girls that knew what family love was and others that never knew; they were taken away as babies.

Some of the staff were cruel to the girls. Punishment was caning or belting and being locked in the box-room or the old morgue... I cannot say from my memories Cootamundra was a happy place.

In the home on Sundays we often went to two different churches, hymns every Sunday night. The Seventh Day Adventist and Salvation Army came through the week. With all the different religions it was very confusing to find out my own personal and religious beliefs throughout my life...

One day the matron called me to her office. She said it was decided by the Board that Kate and myself were to go and live with a lady in a private house. The Board thought we were too 'white' for the home. We were to be used as an experiment and if everything worked out well, more girls would be sent later on. We travelled all day long. Late afternoon we stopped at this house in Narromine. There lived Mrs S., her son and at weekends her husband Lionel...

The Scottish woman hated me because I would not call her 'Mum'. She told everyone I was bad. She made us stay up late sewing, knitting and darning that pillowcase full of endless socks. Often we weren't allowed to bed till after 11 p.m... Mrs S. did not allow me to do homework, therefore my schoolwork suffered and myself - a nervous wreck...

During [my] time [with Mrs. S] I was belted naked repeatedly, whenever she had the urge. She was quite mad. I had to cook, clean, attend to her customers' laundry. I was used and humiliated. The Board knew she was refused anymore white children yet they sent us there.

Near the end of our stay she got Mr F. from Dubbo to visit. She tried to have me put in Parramatta Girls' Home. By this time I knew other people had complained to the Board. Mr F. asked me if I wanted to go to a white home or back to Cootamundra. So a couple of days later we were back in the Home. It was hard to believe we had gotten away from that woman.

It wasn't long after we were back at the Home and Matron called me to her office. She wanted to know what had happened at Narromine. I told her everything. She said the experiment did not work and she would write to the Board for fear they would send more girls out. It did not do any good though because more than half the girls were fostered out over the next three years...

In December 1957 our mother finally got us home. She was the first Aboriginal to move into a Commission house. My mother died four years later, she suffered high blood pressure, she was 54 years old. It was fight all the way to survive because she was born an Aboriginal.

I still can't see why we were taken away from our home. We were not neglected... Our father worked hard and provided for us and we came from a very close and loving family. I feel our childhood has been taken away from us and it has left a big hole in our lives.

- Confidential submission 437 to the National Inquiry into the Separation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Children from their Families, New South Wales

Dear Jennifer,

My name is Tim Rutty and I'm a student at Sherbrook Community School and I have just read your story and was shocked to hear of the torment you have gone through in your stolen childhood. Your letter moved me deep inside of my heart and now my only hope for you is that you are living

happily far from discomfort.

Yours sincerely,

Tim Rutty

Dear Jennifer,

My name is Vonnie, I am almost 15 years old, I go to Sherbrook Community School I live in Cockatoo and I have just finished reading your story. To have been through that must have been horrible. What really disturbed me was Mrs S. when you had to stay up late sewing, knitting and wouldn't let you do your homework! You must have been really strong to have lived through that, from being taken away from your own mother. My nephew, Jack was taken by his mum and my brother has missed his birthday and all. She took him to England and won't be back in months. But my brother is still standing strong. I know that this is nothing like your story. And I wish you didn't have to live through that.

I'm sorry for what you have been through.

From,

Vonnie - Veronica Bingham

Dear Jennifer,

My name is Stephanie Dennis. I am in year 9 and I live in Melbourne with my mum, brothers and sister. My dad doesn't live with us any more, but I still see him some times. I read your story and it really touched and inspired me. If I said I know how you felt I would be lying. I have never felt anything that could almost even compare to the pain you have felt. I have never felt that my land and my people were so closely connected- I have not had “country” to call my familys country. I don't know what it is like to be taken away from home, from the people I love. I am so happy that you got through all that and got to go back home! It was so nice to read your story and know that there are strong women out there who can fight for their rights. Keep on fighting Jennifer! You know you deserve it!

Yours in friendship,

Stephanie. - Stephanie Dennis

Painting: 'Coming Home', Beverley Grant 2007I was put in the Melbourne city Mission, then Torana then back to Melbourne City Mission all before the age of three. After that I went to live with the woman who adopted my mum, who was taken off her mother in the 1930's, under the guise of 'no means of support'. Aboriginal people had little control over their own lives. Our ancestors were told not to speak their own language, and as a result, many of the hundreds of Aboriginal dialects once used have been lost.

Our ancestors, my people, the Yorta Yorta people lived before the arrival of the white man as a civilised society. My great grandmother was a Morgan, a Yorta Yorta Woman. The Yorta Yorta tribe occupied a unique stretch of territory located in what is now known as the Murray-Goulbourn region. At the time of the invasion or before contact the population is estimated to be approximately 2,400. Within the first generation in contact with the European invasion, the Yorta Yorta population was reduced by 85%.

They came to control our ancestors and our land instead of understanding and working with them. This is still continuing today.

- Sandra Barber (Morgan)

At three years of age I was taken from my parents and placed in Wandering Mission in south-west W.A. In the Mission I was in the Choir and like the other kids in the Choir I was doing fine when the word came that we were going to sing in Melbourne, Victoria. This was very exciting for us little Nyoongah kids. Just before the Choir was to go, I was told that I wasn`t good enough and therefore wouldn`t be going on the trip. I was devastated and heart-broken and could only watch with envy as my brothers and sisters inthe Choir waved goodbye as they left to go to Melbourne. After twelve years at the Mission I ran away, at the age of fifteen to find my mother, which I did.

After leaving the Mission I played in Rock and Roll bands and gradually became better at singing and playing music. Ironically, I am the only one out of the Choir that took up music and has progressed to a level where I am now a well-known, capable and qualified musician. Since a teenager I have been playing regularly gigs and have produced a CD album and have also produced a number of CD singles along the way.

In sharing this story I want to give positive encouragement to our Indigenous people. As you can see I was rejected and could have allowed this rejection to dictate my life and could have rejected any notion of ever being a musician. However I didn`t, I turned it around and became exactly what they said that I wasn`t- a good musician. I am now envied and praised by many people and will always love playing music and singing and find it is wonderful therapy that can promote healing.

If someone selfishly tells you that you are not good enough, reject their judgement and turn it around if you know that you are good enough. You don`t have to aim to be the greatest in the world but you can aim to be the greatest that you can be.

- Fred Penny

The Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission, tabled a much needed report to the Federal Australian Government in to the removal practices of past government policies into the Stolen Generations. I am a member of the Stolen Generations.

The Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission Report provided a voice for the Stolen Generations and allowed the wider population of Australia to hear first hand experiences of those whom were taken.

Some people regard the removal practices as genocide a strong word indeed; removal of a generation of children breaks the lineage of families and can be felt throughout generations to come. The effects are enormous on Aboriginal culture and people have lost family, language and culture, therefore results have shown that Indigenous people self medicate to try to lose the trauma and pain associated with their life's experience.

My personal experience of huge trauma was and is an ongoing healing process still conducted today. Merely talking of my experience helps relieve pent up negative emotions and turning these emotions into a positive ones. This journey may not work for everyone , however I am convinced that by addressing the traumatic feelings the journey of healing begins.

I am in my third year of Adult Education at the University of Technology Sydney and when I finish my years of study I will design healing programs for my people who are still on a journey of healing.

Aboriginal people are spiritual beings and by addressing mind / body / spirit then the process of healing can begin. This can be a positive for all Australians on the path to becoming a great nation and country!

- Elaine Turnbull

One Love, One Land

One love, one land, yet we are a race apart.

Ours is the love of a mother

and we speak it from the heart.

For love of our land and its people

and all that it provides,

from desert and forest

and rivers,

wattle myall gum and

gidgee tree-

Possum, kangaroo, dingo

and emu;

Plenty for me and you.

Just 50 years you gave us,

To climb up to where

you are at.

You've had a thousand times more,

so don't blame us for that.

One love - one land between us.

Let's love her as we should,

Teach us how to be better,

and do us all some good!

- Jonathon Cox

I Am To Be

I am to be

The fly at your eye

You just can't brush away

Despite how hard you try.

I am to be

The thorn in your side

Pricking you consistently

Despite all your pride.

I am to be

The dog at your heel

Tenaciously gnawing you

Despite your appeal.

I am to be

Your history's ghost returned

Haunting every moment

Despite your concerns.

I am to be

The disease in your soul

Perpetually rancid

'Til you pay the toll.

I am

The offspring of my ancestors

Baring truths memory

Despite all of yours.

- Yveane Fallon

Jenny Thomas: ``Well, I answered the phone and there was this old lady and she said `May I speak to Eddie please` and I said `may I ask who's calling please?` and she said `Dear, I was in the home that Eddie was in when he got taken away` and she told me her name. So I called Eddie and her name didn`t register and then all of a sudden it clicked who the lady was, but she was seventy- eight and she never ever knew where he went to... `Dear` she said, `I love him, loved him all those years and I have been looking for him all these years.` All those years she did not know where he went, then through the Parliament thing (Tasmanian Stolen Generations Compensation Scheme), he was on the news and she`d seen him. Her son rang her and said `mum have you been watching the news? She said, `by then I was all emotional, because it all brought everything back. She went down and got he number and rang here... So I took him up there and... she told me exactly what went on (in the children`s home in Launceston) and she said `Dear, you have no idea about all the things, it`s all true... And that made Eddie feel that everything was all right now because he could hear someone else telling it how it was and he knew it was true.``

Eddie Thomas: That was the time it all came out for me, because, I did not really want to think about those times. I mean, you know sometimes, you feel when you`re telling adults what happened, and umm, do that believe you? Because it was so awful what happened, you just feel like they can`t believe you. But that lady substantiated for me what I thought had happened there in the home.

- Interview with Janet Drummond.